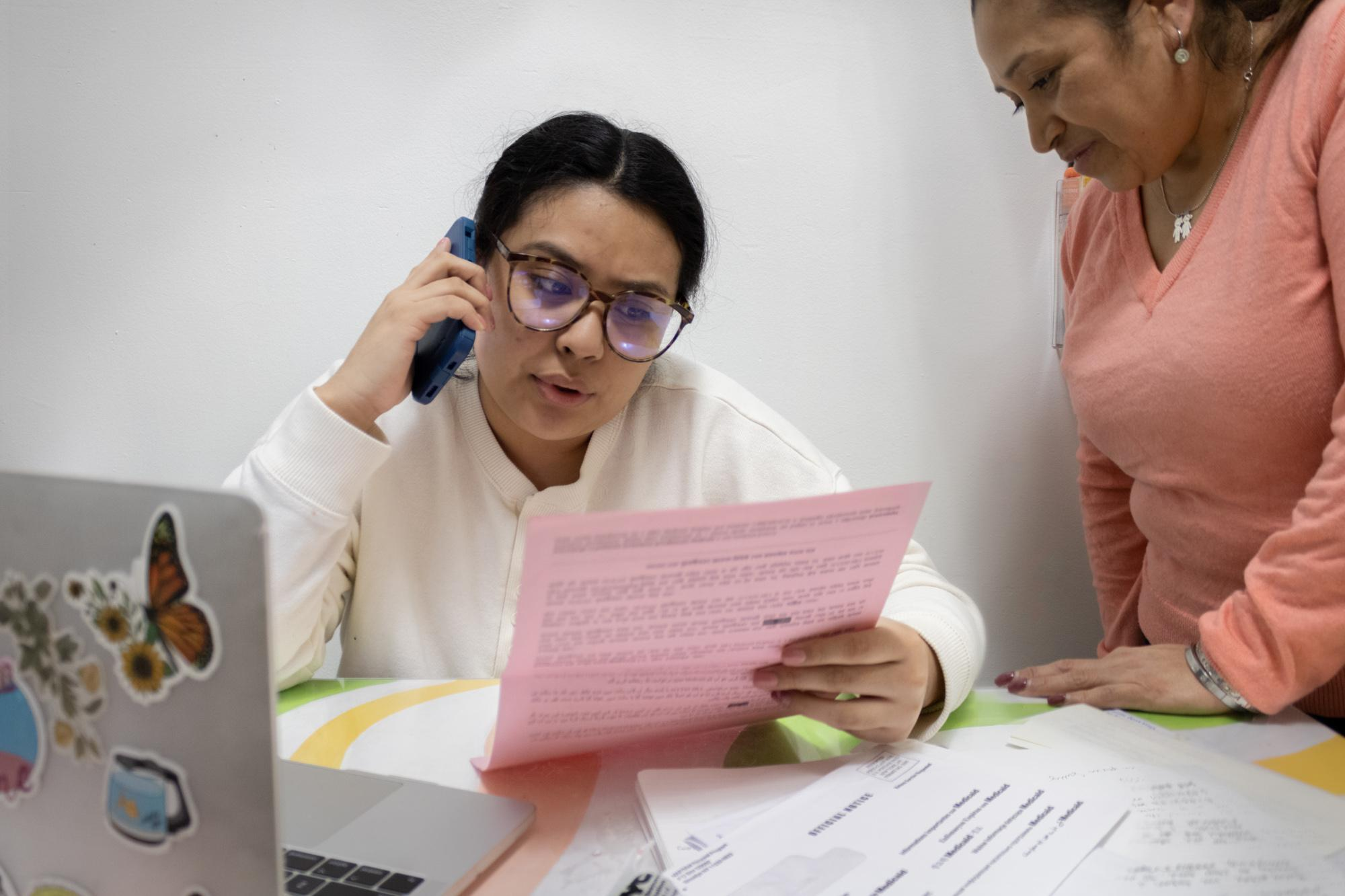

Arecis Tiburcio Zane, 23, is an emerging Mexican photographer and artist based in New York City.

It was a Sunday in June of 2021 when Arecis Tiburcio Zane learned her grandmother, Carmen Gonzalez, had died. The news was two-parted: not only was her grandmother gone, but the most recent time Zane visited her three years prior became the last time she ever would.

“She was very blunt, and very motherly but also not,” Zane tells me with a slight laugh. What seems to be by nature is she open with me — a stranger — about her dead family member. The aura of an old friend lingers through my phone as she walks home from a Harlem elementary school, where she teaches art.

“I like to think I’m not full of shit,” she says, organically, before laughing once more. “I never cared to be a professional artist.”

She is telling the truth, at least of what I can grasp from her assertive yet nonchalant tone. Her statement is not off-par from the style of her photography, which mainly depicts raw moments that appear to a viewer like distant family memories, despite not knowing those in the pictures.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Using her family as her prime subjects, Zane creates out of an intentional randomness, capturing that which is often overlooked as a worthy memory or something eye-catching. Browsing just a few of her photos — Zane’s mother washing her father’s back, Zane’s brother painting her nails, a yellow toy car with wheels designed for toddlers sitting in front of a red sofa chair with a striped blanket — disrupts the luxury of mainstream photography. They are un-concerned about the perfect pose or the perfect setting. Rather, contrary to the mainstream, a shot is extraordinary the more ordinary — and personal — a moment is.

“Family images are often used to look back on special occasions...we take what we see as fact. However, a lot of what we remember isn’t true,” Zane’s website reads. “So much happens outside of what’s shown in an image. That’s why I enjoy creating my own.”

Arecis Tiburcio Zane. © Arecis Tiburcio Zane

On social media, Zane labels herself a ‘professional over-sharer.’ Her Instagram is flooded with fragments of past and future art pieces, moments and everyday happenings. In very few posts is she posing, and in even fewer is she in at all. Similarly, that randomness is reflected in her portfolio. A section titled “Notes” resembles a pile of random photos in a drawer, where a viewer can interact with them and drag them around in any order.

“I’m sometimes a planner. But when it comes to my art, I don’t worry about it,” Zane tells me. “My thoughts can’t be wrong if they are from the heart.”

But there is a not-so-obvious challenge to Zane’s works, despite her seemingly impulsive authenticity. “The easiest and hardest people to photograph are your family,” says Zane. “An art teacher told me that.”

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Three of Zane’s artworks have been exhibited in galleries and featured in online showcases within the last two years.

In 2022, one of her photographs was featured in the online showcase, A Feel for the Place. A separate project, “No Vivo de Recuerdos” — a series of portraits Zane altered to mirror and sometimes replace her other family members — was exhibited at a winter conference for the Sociologists for Women in Society, an international feminist organization. In 2021, another photo from that series was exhibited in This Was the Year That Was, an art show hosted by the International Center of Photography in New York.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

But having been born and raised in Hamilton Heights to two immigrant parents, Zane has had to learn to balance her love of art with her parents’ fears over pursuing it as a career. “The role reversals and even role sharing allow me to understand my contribution as the eldest child in an immigrant family,” Zane writes on her website.

Rather than crack from pressures of success and financial stability, however, Zane finds inspiration in them. By analyzing her family as subjects, she comes to know the meaning of her own identity.

"They are more than just photos,” says Zane, her voice deep with sincerity.

“I am creating as a form of rebellion.”

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Zane was twelve when she first started photographing. At the New Jersey Apple Farm Arts Camp one summer, she peeled from her painting and print-making majors to take a shot at photography. At first, she struggled with aperture — the opening of the camera’s lens which lets light pass through. She held a mini photography show and realized too late that all of her photos had been over-exposed.

“But I was so happy that I got pictures of my friends,” Zane tells me. “And was able to create something from scratch.”

During her junior year of high school, she couldn’t afford a film camera and borrowed one from her school, instead: “a super heavy Canon AE1 that pokes you and has its straps falling apart. I still use it,” she says, matter-of-factly.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

I ask her what she photographed with it then, and she tells me flowers. “That was because they wouldn’t move, and I wasn’t too good with shutter speed. Then I moved to digital and took pictures of the people I love.”

When it was time to decide on a college major, Zane chose education. “I always wanted to be some sort of teacher,” she shares. But soon into her freshman year, she took a course on black and white film and later switched her major to photography. She continues, “Pursuing art in higher education was a form of rebellion in and of itself.”

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Many of Zane's pieces trigger a sense of nostalgia, a longing for the simple moments spent with loved ones that we often forget. By placing components of her own personal relationships with her family members front and center, Zane's work is a catalyst for viewers to ponder about how snapshots of our own moments spent with loved ones would represent our relationships, and whether they are accurate.

It was these senses of nostalgia and reflection that poured over me when I first laid eyes on “On Sunday,” Zane’s latest gallery work showcased as part of her art thesis during the last semester of our university careers. The photo-based, multimedia project uses family images, letters and memorabilia to explore Zane’s grief in losing her grandparents.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

“I am using images to trigger memories from my parents,” she writes in the project’s description. And it was no one other than Gonzalez— her very-blunt-very-motherly-but-also-not grandmother who had a kind honesty — who was the project's creational push.

“She asked me if I was curious,” Zane says, undistracted as car horns blare and echo beside her voice in a noisy chaos. She is in a memory; the time Gonzalez asked her if she was ever curious about their family’s origins in Coyahualco, Mexico. She admits it was a question too immersive to ponder for only one day to her — an NYC-born, Mexican-American who learned deviations from traditional Mexican cuisine. She fell in love with spaghetti and meatballs, and her grandmother — despite never living in the United States and certainly not Italy — cooked the dish with priority for her and her brother when they visited Mexico.

“Food from a whole different country,” Zane says with emphasis. She learned her grandmother’s connection to her went beyond distance, limited visits and the single culture Gonzalez was surrounded by for her entire life: “She knew things about us that I didn’t expect her to know.”

Zane's grandmother's last batch of hot cocoa. © Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Zane doesn’t explicitly say it out loud, but she shares something with Gonzalez, who taught her to make Mexican hot chocolate using cocoa, sugar, cinnamon and a rusty, metal handheld tool. That thing they share, like the cocoa, grew naturally from their heritage. And like the rusty, metal handheld tool Zane now protects in her bedroom drawer as a safe-keep, that thing they share is also prized. Between the two of them, making things for one another was its own love language.

“Throughout all of my childhood, she would send us hot chocolate in the mail,” Zane says, warmly. “Now the last batch she made is in a special container. No one will drink it.”

After Gonzalez's death, “On Sunday” sat for three months without a finger lift from Zane. “I felt like I couldn’t move forward with it, I couldn’t move on. But the memories were still there,” she tells me.

Her tone evokes an image of a familiar deflation — the heartbreaking moment when an artist diverges from their art. Zane is honest from the forefront about it — that photography, though something she loves dearly, is also something she has pushed away. She did so until one weekend in September of that same year, when her grandfather and Gonzalez’s spouse, Panuncio Tiburcio passed away hours after Sunday mass.

“I had a feeling it was going to be the last time,” Zane says. That feeling grew as she grieved, and soon it became a need: Zane was curious about her family’s history. She knew she was when Gonzalez had asked, but it was complicated, “I had to navigate grandparents differently than most people.”

When she was a child, her grandfather on her mother’s side died, leaving Zane to only speculate what he was like. “I couldn’t process the concept of death, I just knew there were no more memories,” she explains. She has an idea of who she thinks her grandfather would have been had he survived to her adulthood. But she feels, sometimes, that “he is only a figment of my imagination.” For her, not knowing is a loss of its own. But it isn’t always under her control — her grandmother on her mother’s side, who Zane didn’t meet until her teenage years, has always been a little bit “closed off.”

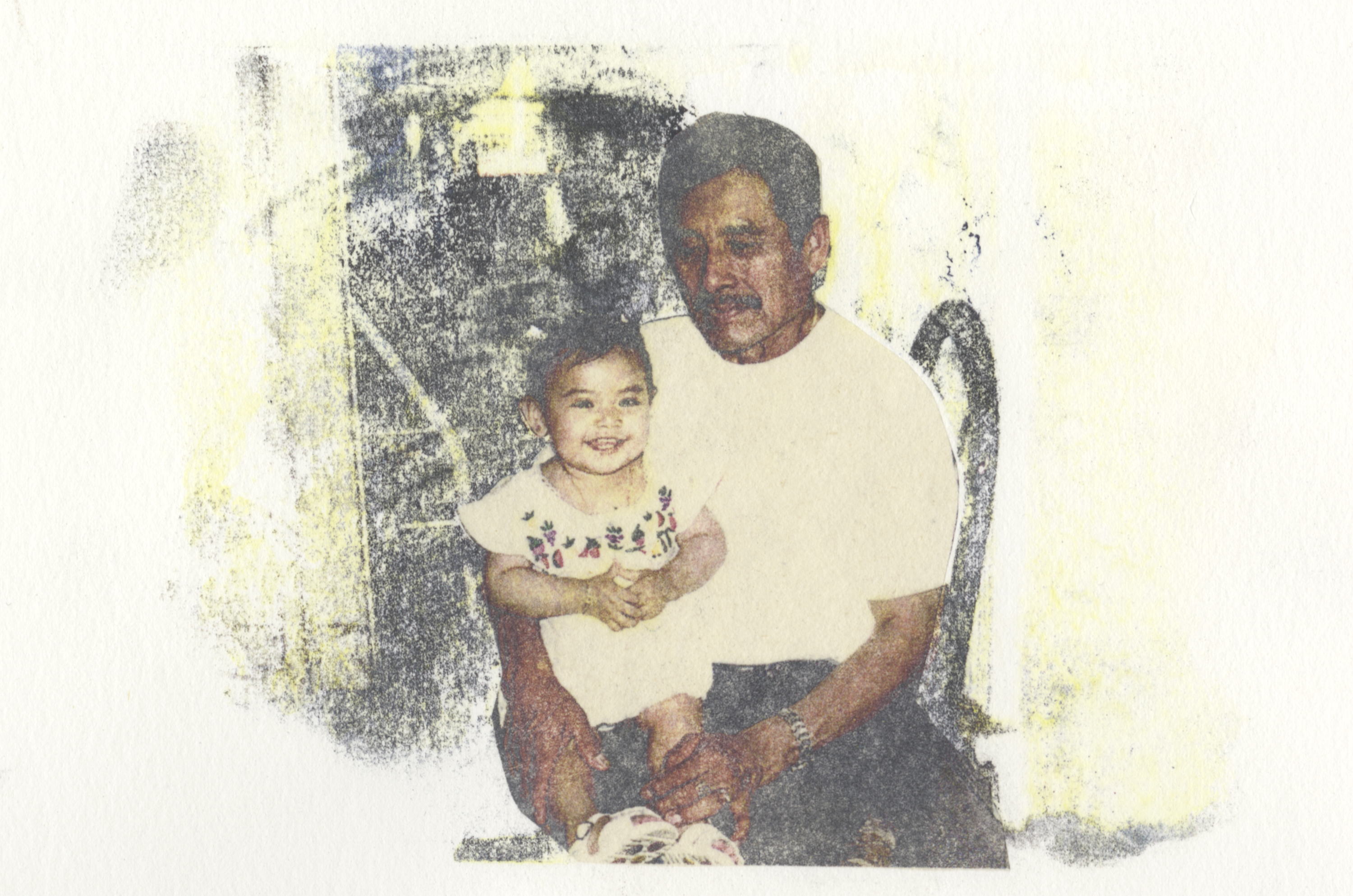

She hit a turning point when Tiburcio, the man whose lap was like a safety cushion for her baby self, passed along, too. She tells me there’s a photo of it: the moment one day when, after she wouldn’t stop crying no matter what her mother tried, Tiburcio picked Zane up and seated her on his thighs. Almost instantly, Zane’s tears slowed to a stop, her tiny mouth corners curved upward into a smile. “That’s how much I loved my grandpa,” she says, warmly.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Tiburcio migrated to the U.S. in the early 1990s in search of work. The money he made was sent back to Mexico to build a new house for Gonzalez. He farmed oranges in Florida before moving to New York to work in a factory owned by Sweet’N Low, the famous low-calorie sugar company. Tiburcio had previously been to the U.S. in the 40s, where he stayed for twenty years before returning back to Mexico.

“That was a big chunk of their marriage where they weren’t even together,” Zane says of him and Gonzalez. “But their relationship was always good. You know in Latino households, machismo is a huge thing,” she says with a deeper tone, then lightening up again. “But they were never like that. Grandma didn’t take bullshit, and grandpa was chill. He never complained. He was so strong without having to say anything.”

When Gonzalez passed away, Tiburcio never admitted his sadness to family. His neighbor’s son noticed him crying once atop the mountainous area they lived in in Coyahualco. “I really miss Carmen,” Tiburcio told him.

“I wondered why when he was still alive he didn’t tell us,” Zane says, reminiscently. “He never wanted to burden anyone.”

When Tiburcio passed, the memories Zane had of her grandfather and the knowledge of his sacrifices mixed to form their own version of responsibility.

“I had to do the project,” she says. “Their deaths pushed me to start talking about things I was uncomfortable talking about.” Things like death and loss, but also the intricacies of family relationships, migration and how they impact one another. “I hate that he had to come here,” she continues. “And it was important that I didn’t romanticize his migration story.”

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

At first glance, “On Sunday” resembles a family living room that’s wall has been covered in family photos. A red sofa chair’s ends sit with reaching threads of a black, red, yellow and green carpet. Leaning on the chair are a pair of brown cowboy boots that have been stitched with a falcon-wing pattern. A closer look at the photos on the wall shows the boots are the same ones as those in one of the photos. Whose life was I looking at? And why did it feel so familiar?

I learned that Zane’s dependence on authenticity is what makes her art feel so close to home. From the color of the wall paint — a "wasabi green" that reminds her of her parent's first apartment — to the mismatched frames — because "realistically, would someone go out of their way to find the perfect frame for a family photo?" she wondered — she welcomes us into a replica of her own family living room.

"A color can have so much power," she tells me. "The color green feels like home. It brings peace to me. When I visited my parents' hometown, there was so much green. It almost felt like everything was a circle."

A stack of the photos contain objects and people who have been added or removed using digital alterations and what Zane calls “crude” cutouts. Others are altered from a solvent image-transfer, a printing process that “borrows” subject matter from a printed material and chemically dissolves it before transferring it onto a new surface. For Zane, these alterations create memories she “wished had happened.”

One photo titled, “Me, Jesus, Dad and Grandpa” is digitally altered to include an older version of Zane’s younger brother posing for a family photo with her toddler self, her father and Tiburcio. At the time the original photo was taken, Zane’s brother was not yet born.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Another photo titled, “Grandpas House Upper West Side” was transferred onto a white piece of paper and shows a toddler Zane cut out from a picture of her at Tiburcio’s house, leaving a white space in the center of the photo. The cutout is printed in the bottom right corner of the paper, her younger body dressed in a jean jacket, red shirt and pair of jean overalls, pasted against the white nothingness around her. Her younger self’s ankles dissipate before her feet can be printed — evermore nostalgic over how she is no longer in her grandfather’s house, and will never set foot inside of it again.

© Arecis Tiburcio Zane

Other photos are of locations Zane revisited after being told stories from her parents’ adolescence and her grandparents’ lives, and by capturing them, Zane’s given herself a pass to endlessly retell them.

“There’s a river my parents crossed to get to each other’s towns back in Mexico,” she says with fascination. “Here in New York, there are places I found that were similar. They were different, of course, but they felt the same.”

Zane found that, with a bit of imagination, and a bit of exploration, she could create a world where borders didn’t exist, and where home was everywhere.

“This was a project for school, but for me, it’s about their life. It’s about life,” Zane says. “It’s about how I am continuing to live—through them..."

Zane does with art what many children of migration stories must figure out how to do in their own lives — piece together their origins. But Zane seems to welcome the difficulty and pain. If anything, it feels to her like a natural part of her art-making process. “On Sunday” was a way for her to process all of that grief as one, and memorialize her grandparents who created a vast amount of memories that could be copied and pasted throughout their family's generations.

Zane continues, "...It's about how I’m going to keep talking about what they’ve taught me.”